At Zerodha, many million users login and use our financial platforms every day. Over the recent months, on an average day, 1.5+ million users have been executing stock and derivative transactions. On a volatile day, this number could easily double. After a trading session concludes and all the number-crunching, tallying, and “backoffice” operations are completed—with file dumps received from stock exchanges and other market infrastructure institutions—stock brokers e-mail a digitally signed PDF report called the contract note to every user who transacted on that particular day. This PDF report offers a comprehensive breakdown of each trade, detailing the total cost associated with each transaction. Its layout, contents, delivery time, and all other aspects are bound by regulations.

Needless to say, this is a complex task to orchestrate at scale. Our legacy system which we had been continually improving over the years, had grown to taking some 8 hours daily, at which point a complete overhaul was required. We typically watch technical debt closely and allow it to grow to a certain acceptable level before addressing it. For this trade-off, we pause development of new features when necessary for the sake of the overall health of our stack.

TL;DR: In this blog post, we describe our journey of rethinking the architecture and building an architecture from scratch which now enables us to process, generate, digitally sign, and e-mail out 1.5+ million PDF contract notes in about 25 minutes, incurring only negligible costs. We self-host all elements of this architecture relying on raw EC2 instances for compute and S3 for ephemeral storage. In addition, the concepts used for orchestration of this particular workflow can now be used for orchestrating many different kinds of distributed jobs within our infrastructure.

Old stack

- A Python application reads various end-of-the-day CSV dumps coming from exchanges to generate HTML using a Jinja template.

- Chrome, via Puppeteer, converts this HTML into PDF format.

- A Java-based command-line interface (CLI) tool is then used to digitally sign the PDFs.

- Self hosted Postal SMTP servers to send signed PDFs over email.

Before the revamp, the entire process took between 7 to 8 hours to complete, with durations extending even longer on particularly high-volume days. These processes ran on a large single, vertically scaled server that would be spawned for the duration of the work. As the volume of work grew over time, the challenges increased. Additionally, the self-hosted Postal SMTP server started hitting significant performance bottlenecks further affecting the throughput.

The necessity to send these contract notes before the start of the subsequent trading day added significant pressure, as the computation of source data itself is time-consuming and reliant on the timely receipt of various files from exchanges, which themselves experience delays. So, we really had to throw away what we had and think afresh.

New design

It was clear that the only way forward was a horizontally scalable architecture, enabling us to add more capacity as required indefinitely (theoretically at least). Given that stock market volatility can cause the workloads to vary wildly on a daily basis, we had to come up with a system that was not only highly performant and resource efficient, but time bound, thanks to regulations. A conventional FaaS (“Functions as a Service”) offering with cold-start problems and communications overhead, and of course cost overhead per run, would not be ideal. To get large volumes of CPU-bound work done as quickly as possible, going by first principles, for this usecase, it made sense to take a strategy where we would spin up large ephemeral server instances whose CPU cores would be saturated concurrently with work with little time spent on waiting. On completion, the instances could be destroyed immediately, thus gaining optimum resource usage and costing.

In this particular case, the contract note PDF generation workflow is composed of many independent units of work with varying resource requirements. Data processing -> PDF generation -> PDF signing -> e-mailing PDFs, all of which can have independent workers doing their respective jobs and passing the results back into the pool to be picked up by another worker. Since the goal is high throughput and optimum utilisation of available resources, apart from designating CPU pools for different job groups, fine grained resource planning is not necessary. In fact, any sort of granular resource planning is not feasible as the size and scale of individual workloads can vary wildly on a daily basis. One user could have a PDF report with two pages while another could have two thousand pages. So the best bet is to throw all the jobs into a pool of workers running on large ephemeral instances and wait for the last job to be done before tearing down the instances. That one two-thousand page PDF customer on a volatile market day may hold up a core 100 times longer than another customer, but because we spawn a large number of cores and burn through the jobs concurrently, it evens out. This approach worked out really well for us.

Architecture

To begin with, we rewrote the Python worker process from scratch as concurrent Go programs, immediately availing performance and resource usage benefits by orders of magnitude. For distributing job processing between various worker instances, after evaluating existing options, we ended up writing a lightweight, pluggable Go messaging and job management library—Tasqueue.

// Pseudocode.

func generatePDF(b []byte, c tasqueue.JobCtx) error {

// ...

c.Save(result)

return nil

}

// Register job functions.

srv.RegisterTask("generate_pdf", generatePDF, TaskOpts{})

// Register a chain of jobs.

chain = []tasqueue.Job{

tasqueue.NewJob("generate_pdf", payload),

tasqueue.NewJob("sign_pdf", payload),

tasqueue.NewJob("email", payload),

}

tasqueue.NewChain(chain, tasqueue.ChainOpts{})

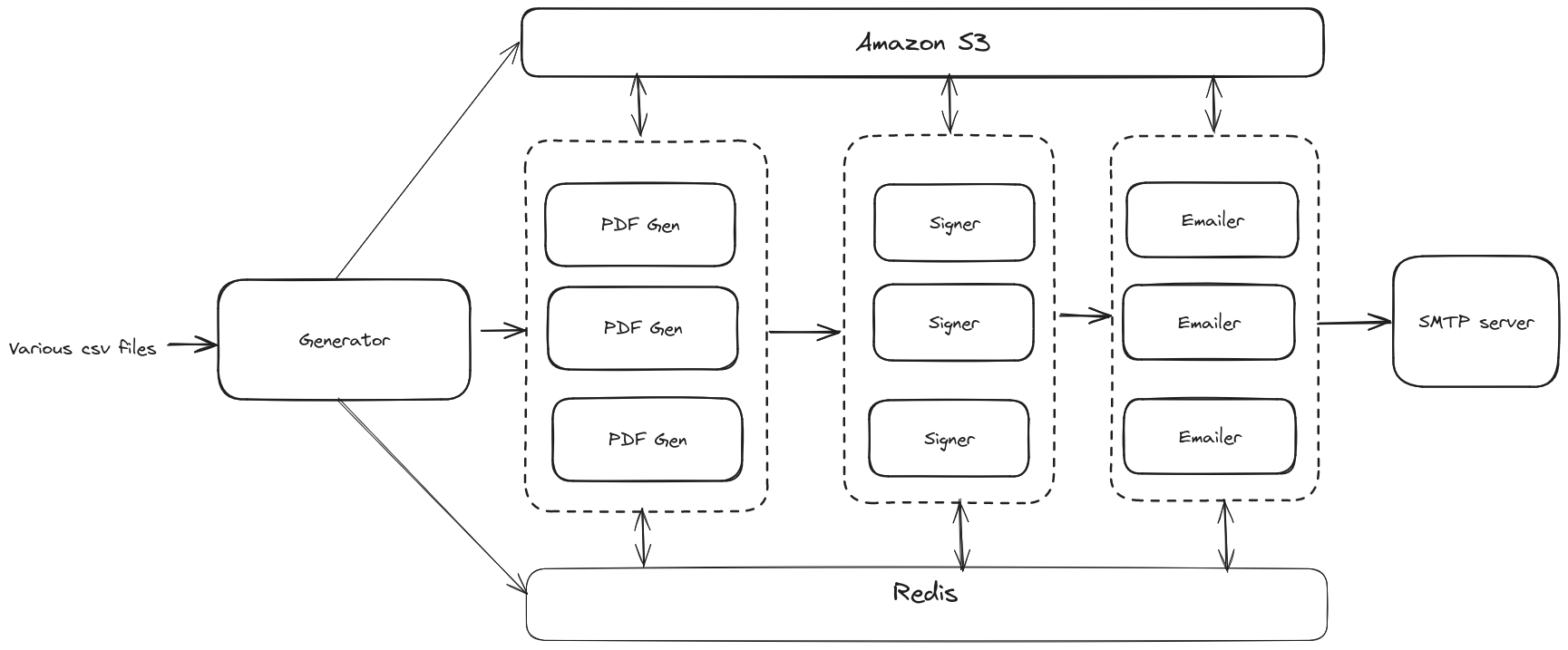

The first sequence in our chained jobs workflow begins with a generator worker processing various CSV files to create templates for PDF files. This is then pushed into the queue as a job for the next worker, say the PDF generator, to pick up. Various different kinds of workers upon picking up their designated jobs, retrieve the relevant file from S3, process it, and then upload the output back to S3. So, for a user’s contract note PDF to be delivered to them via e-mail, their data passes through four workers (process data -> generate PDF -> sign PDF -> e-mail PDF), where each worker after doing its job, dumps the resultant file to S3 for the next worker to pick up.

The global job states are stored in a Redis instance. It serves a dual role in this architecture: as a backend broker facilitating the distribution of jobs among workers and as a storage medium for the status of each job. By querying Redis, we can track the number of jobs processed or identify any failures. For jobs that fail, targeted retries are initiated for users whose jobs previously failed or were not processed.

Generating PDFs

Initially, PDFs were generated from HTML using Puppeteer, which involved spawning headless instances of Chrome. This of course grew to be slow and quite resource-intensive as our volume grew.

After several experiments including benchmarking PDF generation with complex layouts using native libraries in different programming languages, we had a breakthrough using LaTeX instead of HTML and generating PDFs using pdflatex. By converting our HTML templates into TEX formats and utilizing pdflatex for PDF generation, we observed a 10X increase in speed compared to the original Puppeteer way of generating. Moreover, pdflatex required significantly fewer resources, making it a much leaner solution for our PDF generation needs.

Problems with LaTeX

We rewrote our PDF generation pipeline to use pdflatex and ran this in production for a couple of months. While we were happy with the significant performance gains with LaTeX, this process had its own challenges:

- Memory Constraints with pdflatex: For some of our prolific users, the PDF contract note extends to thousand pages as mentioned earlier. Generating such large documents leads to significantly higher memory usage. pdflatex lacks support for dynamic memory allocation, and despite attempts to tweak its parameters, we continued to face limitations in terms of memory usage.

- Switch to lualatex: In search of a better solution, we transitioned to lualatex, another TeX to PDF converter known for its ability to dynamically allocate more memory. lualatex resolved the memory issue to a considerable extent for large reports. However, while rendering such large tables, it sometimes broke and produced indecipherable stack traces which were very challenging to understand and debug.

- Docker image size: We were using Docker images for these tools, but they were quite large thanks to the required TeX libraries for both pdflatex and lualatex, along with their various 3rd party packages. Even with caching layers, the large size of these images resulted in delayed startup time for our instances on a fresh boot up before our workers could run.

In our search for a better solution, we stumbled upon Typst and began to evaluate it as a potential replacement for LaTeX.

Typst - a modern typesetting system

Typst is a single binary application written in Rust that offers several advantages over LaTeX.

- Ease of Use: Typst offers a more user-friendly developer experience compared to LaTeX, offering a simpler and consistent styling experience without the need for numerous third-party packages.

- Error Handling: It provides better error messages making debugging any such issues related to bad input data significantly easier.

- Performance: In our benchmarks, Typst performed be 2 to 3 times faster than LaTeX when compiling small files to PDF. For larger documents, such as those with tables extending over thousands of pages, Typst dramatically outperforms lualatex. A 2000-page contract note takes approximately 1 minute to compile with Typst, in stark contrast to lualatex’s 18 minutes.

- Reduced docker image size: Since Typst is a small statically linked binary, the Docker image size reduced significantly compared to bundling lualatex/pdflatex, improving the startup time of our worker servers.

Digitally signing PDFs

Regulations mandate that contract note PDFs should be digitally signed and encrypted. At the time of writing this, we have not found any performance-focused FOSS libraries that can batch sign PDFs, thanks to the immense complexities in PDF digital signatures. We ended up writing a small HTTP wrapper on top of the Java OpenPDF library, enabling a single boot JVM which can then handle signing requests concurrently. We deploy this server as a sidecar alongside each of our signer workers.

Generating and storing files at high-throughput

The distributed contract note generation workflow processes client and transaction data, generating PDF files typically ranging from 100kb to 200kb per user, where the PDFs can also run into MBs for certain users. On an average day throughout the workflow, this comes up to some 7 million ephemeral files that are generated and accessed throughout the workflow (Typst markup files, PDFs, signed PDFs etc.). Each job’s execution is distributed across an arbitrary number of EC2 instances and requires access to temporary input data from the preceding process. Shared storage allows each process to write its output to a common storage area, enabling subsequent processes to retrieve these files, eliminating the need to transfer files back and forth between job workers over the network.

We evaluated AWS’ EFS (Elastic File System) in two different modes: General Purpose mode and Max I/O mode. Initially, our tests revealed limited throughput as our benchmark data was relatively small. Without specified throughput provisioning, EFS imposes a throughput limit based on data size. Consequently, we adjusted our benchmark setup and set the provisioned throughput to 512Mb/s.

Our benchmark involved concurrently reading and writing 10,000 files, each sized between 100kb and 200kb.

- In General Purpose mode, we reached the EFS file operation limit (35k ops/sec, with reads counting as 1 and writes as 5) and experienced latencies resulting in 4-5 seconds to write these files to EFS.

- Performance deteriorated in Max I/O mode, taking 17-18 seconds due to increased latency. We dismissed Max I/O mode from our considerations due to its high latency.

Given the large number of small files, EFS seemed wholly unsuitable for our purpose. For comparison, performing the same task with EBS took approximately 400 milliseconds.

We revised our benchmark setup and experimented with storing the files on S3, which took around 4-5 seconds for a similar number of files. Additionally, we considered the cost differences between EFS and S3. With 1TB of storage and 512Mb/s provisioned throughput, S3’s pricing was significantly lower. Consequently, we opted to store our files on S3 rather than EFS, given its cost-effectiveness and the operational limitations of EFS.

We also consulted with the AWS Storage team, who recommended exploring FSx as an alternative. FSx offers various file storage solutions, particularly FSx for Lustre, which is commonly used in HPC environments. However, since FSx was complicated to set up and unavailable in the ap-south-1 region during our experimentation—coupled with our operations being restricted to this region—we opted for S3 for its ease of management.

We rewrote our storage interface to use S3 (using the zero-dependency lightweight simples3 library which we developed in the past), but hit another challenge this time: S3 Rate Limits. S3’s distributed architecture imposes request rate limits to ensure fair resource distribution among users.

Here are the specifics of the limits:

- PUT/COPY/POST/DELETE Requests: Up to 3,500 requests per second per prefix.

- GET/HEAD Requests: Up to 5,500 requests per second per prefix.

When these limits are exceeded, S3 returns 503 Slow Down errors. While these errors can be retried, the sporadic and bursty nature of our workload meant that we frequently encountered rate limits, even with a retry strategy of 10 attempts. In a trial run, we processed approximately 1.61 million requests within a 5-minute span, averaging around 5.3k requests per second, with an error rate of about 0.13%. According to the AWS documentation, to address this challenge, the bucket can be organized using unique prefixes to distribute the load.

Initially, for each customer’s contract note, we generated a unique ksuid. These are not only sortable but also share a common prefix. Eg:

bucket/2CTgQKodxGCCXxXQ2XlNyrVSFIV

bucket/2CTgQKtyZ2O9NGvt1gSo75h5N9V/

bucket/2CTgQKwBQasuWHaz1QnOIWDNrtc/

bucket/2CTgQKyEGGhk006bgTXErNyu0NE/

bucket/2CTgQL3U7griLK2tyHDOLiYe7w4/

bucket/2CTgQL5FRLfyvwnZazwzVJ55vN4

bucket/2CTgQL5VmmofACvSf3IEuZNvMwL

bucket/2CTgQL8Vc6eTq2t8QyS3BJcClMV/

After consulting with our AWS support team to understand why we were encountering rate limitations despite creating unique prefixes, we discovered that the bulk of our requests were being directed to the same partition, 2CTgQ.

Each new partition increases the allowable request rate by an additional 3.5k for non-GET requests and 5.5k for GET requests per second. This scaling process continues until the prefix structure cannot accommodate further expansion. If we send requests across a completely different prefix next time, for example, bucket/3BRgJLV/, the same process will start for this prefix as well, while the partition that was created across 2CTgQ would be running cold. When a specific partition runs cold, the partitioning process would need to start over when request rates are high again. Thus, to fully benefit from S3’s partitioning capabilities, it is crucial to consistently utilize prefixes that have already been partitioned to achieve higher transactions per second (TPS). Armed with this knowledge from the AWS support team, we opted to revise our partitioning schema, moving away from the use of ksuid.

We ended up with a simple, fixed schema: {0-9}-{pdfs, signed_pdfs, contract_notes}.

bucket/1-contract-notes-data/

bucket/1-tmp-pdf/

bucket/1-signed-pdf/

...

bucket/2-contract-notes-data/

bucket/2-tmp-pdf/

bucket/2-signed-pdf/

...

bucket/9-contract-notes-data/

bucket/9-tmp-pdf/

bucket/9-signed-pdf/

With this, all API requests are now evenly distributed across these 10 fixed partition keys, effectively multiplying our original rate limits per key by tenfold. Furthermore, we requested AWS to have the partitions in our S3 bucket be pre-warmed. Given the nature of our operations—a batch job with a high throughput and bursty request rates—we anticipated potential cold start issues if a partition key weren’t already allocated to handle a high volume of requests. We specifically want to thank the AWS S3 team here for the deep-dive.

Orchestrating with Nomad

We chose Nomad as the foundation for our orchestration framework as all our deployments at Zerodha already use Nomad. We actually like it and understand it well, and it is far easier to run and use as an orchestrator than something like Kubernetes.

We use the Terraform module which we developed to provision a fresh Nomad cluster (including server and client nodes) every midnight before running the batch job process. Here’s an example of how we invoke a Nomad client module:

module "nomad_client_worker_pdf" {

source = "git::https://github.com/zerodha/nomad-cluster-setup//modules/nomad-clients?ref=v1.1.5"

cluster_name = local.cluster_name

nomad_join_tag_value = local.cluster_name

nomad_acl_enable = true

client_name = "worker-pdf"

enable_docker_plugin = true

ami = local.ami

override_instance_types = var.worker_pdf_client_instance_types

instance_desired_count = var.worker_pdf_client_instance_count

vpc = local.vpc

subnets = local.subnets

default_iam_policies = local.default_iam_policies

client_security_groups = local.default_security_groups

wait_for_capacity_timeout = "30"

}

This module facilitates the setup of all essential infrastructure including launch templates, Auto Scaling Groups (ASGs), IAM roles, and security groups, required to deploy the ephemeral fleet of nodes that we use to process the bulk jobs. We utilize multiple ASGs, each handling load for different groups of servers handling different jobs such as signing PDFs, sending emails, and generating PDFs.

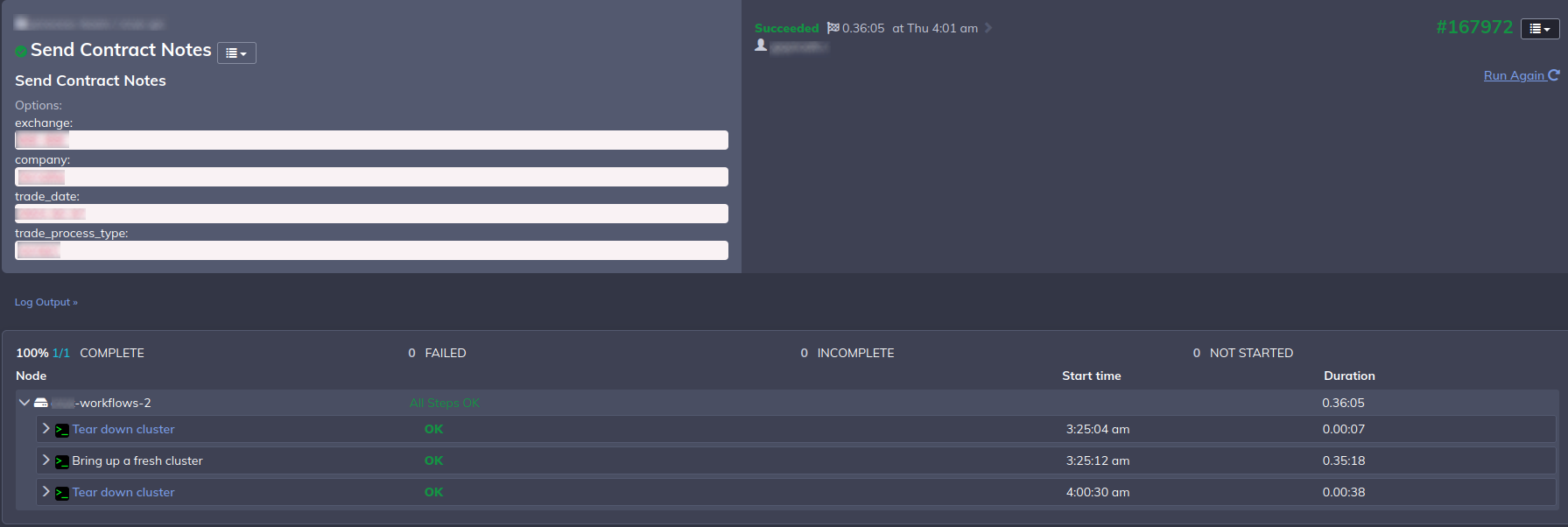

For the admin management and execution, we rely on a small control instance server that is equipped with Rundeck for orchestrating the entire workflow, from infrastructure creation to job execution and completion.

Execution

The control instance serves as the central orchestrator, executing scripts across three key phases of the batch job:

Initialization: The process starts by running a Terraform pipeline to launch both Nomad server and client nodes. The client nodes are where our job workers will run. Upon cluster readiness, the script verifies that all nodes are eligible for scheduling jobs by the Nomad scheduler before proceeding.

Job Deployment: Once the nodes are up, Nomad deploys our job worker programs (Go binaries pulled from S3 for the most part) on designated nodes, where they listen for incoming jobs, enabled by the distributed task management library.

Nomad offers various scheduling strategies suited for diverse workload types. For our needs, system jobs proved particularly valuable. Like Kubernetes’ DaemonSets, system jobs ensure that one instance of the job runs on each node, guaranteed by the Nomad scheduler.

job "worker" {

datacenters = ["contract-notes"]

namespace = "batch-workflows"

type = "system"

group "pdf-creator" {

count = 1

constraint {

attribute = "${meta.ec2_nomad_client}"

operator = "="

value = "worker-pdf"

}

}

group "cn-worker-signer" {

count = 1

constraint {

attribute = "${meta.ec2_nomad_client}"

operator = "="

value = "worker-signer"

}

}

}

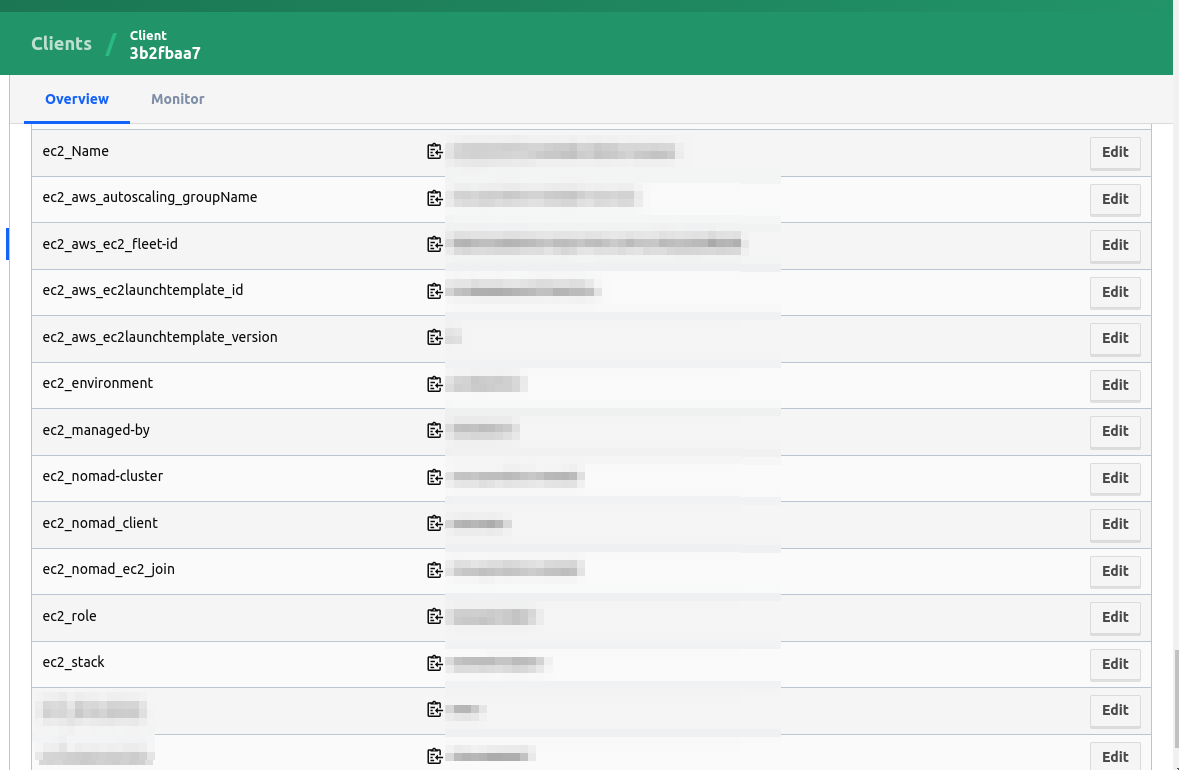

Beyond utilizing system jobs, we also use the constraints stanza for further control over worker placement. Through our Terraform module, we pre-populate EC2 tags within the Nomad client configuration, making these tags accessible within Nomad’s client meta. These tags then serve as the basis for defining constraints, enabling dynamic job scheduling and node assignment based on specific attributes.

Using the nomad_client EC2 tag, we determine the role of each client and deploy the corresponding program, which for the most part, are our worker programs written in Go. In the example above, you can see separate ASGs for signer and pdf-creator tasks. This enables Nomad to ensure they run on distinct sets of nodes for optimal resource utilization.

PDF generation requires significantly more resources than signing tasks, so we use separate ASGs for these processes to scale them independently of other jobs.

Once jobs are initiated, we additionally stream the job statuses to the RunDeck UI from the Redis instance that maintains the global state of all distributed jobs, in case an admin wants to peek.

The Rundeck control server runs a Python script to extract job status data from Redis:

all_cnotes_str = r.get( f"batch-workflows:cnote:all:{posting_date}:{exchange}:{company}:{trade_process_type}"

)

For the contract note generation job, we spawn about 40 instances in total currently, a mix of c6a.8xlarge, c6a.2xlarge, and c6a.4xlarge.

Post-execution teardown

Upon the completion of all queued jobs—in this example, the computation, generation, signing, and e-mailing of 1.5+ million PDFs—we initiate the teardown process. A program that monitors the successful job count in the Redis state store executes this by simply invoking a terraform teardown. This involves resetting the ASG counts to zero, draining existing nodes, halting Nomad jobs, and shutting down the Nomad server itself.

In this specific example, the entire operation, end-to-end, finishes in 25 minutes. The cost incurred is unsurprisingly, negligible.

E-mailing PDFs at high-throughput

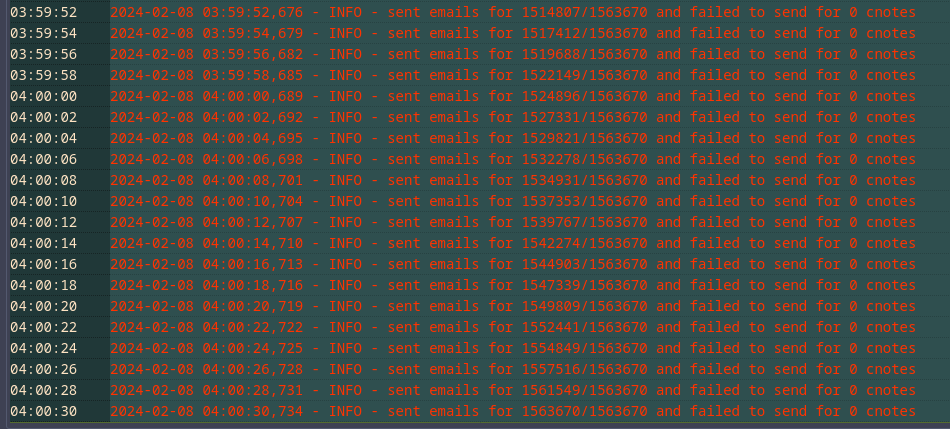

As PDF signing workers sign PDFs and hand them over, they are instantly queued for being e-mailed by the e-mailing workers. We use a self-hosted auto-scaling Haraka SMTP server cluster and maintain concurrent connection pools from the e-email workers with the smtppool library we wrote to push out e-mails at high throughput.

We transitioned from Postal that we used for many years to Haraka for significant performance benefits—a change that merits its own post separately. Postal’s resource usage was intense and it was not horizontally scalable, and unfortunately grew into an unfixable bottleneck. However, with our move to Haraka which can be easily horizontally scaled, we are no longer limited in capacity pushing out e-mails from our SMTP cluster to target mail servers over the internet. It is important to note that IP reputation matters when self-hosting SMTP servers and we have grown and maintained this over almost a decade—mainly by never sending marketing e-mails and definitely not spam!.

Conclusion

So, that’s it. We are very pleased by the throughput that we have achieved with the new architecture, primarily with the breakthroughs that are Typst and Haraka, and all the orchestration headaches that Nomad trivially handles for us. This is not one big software system, but more of a conceptual collection of small scripts and programs that orchestrate workflows for our specific bulk jobs. We are also happy that this also resulted in the creation and open sourcing of multiple projects.

We plan on moving all our time consuming bulk jobs—of which there are plenty in our industry—to follow the same framework. In addition, we are in the process of adding metrics to the workers so that we can track the global workflow states in realtime and adjust resources as necessary.

As the architecture is simple and rooted in common sense practices conceptually, the fundamental building blocks can be swapped out entirely if required (RunDeck, Nomad, S3 etc.). We are confident that this will do its job and scale well for a long time, and there is room for further optimisation. Needless to say, spawning a few large barebones instances, running highly concurrent business logic saturating all cores throughout and then winding down as quickly as possible, the cost incurred is negligible, and any potential resource wastage is minimal, if not nil.