At Zerodha, we process millions of trades in real-time, where each trade comes into the system as concurrent high throughput HTTP requests. Each trade increases the latency for subsequent orders in the queue that are under processing at the same time at our OMS (Order Management System). When a single order comes through to the OMS, it goes through a bunch of computationally intensive validations and adds to the latency. To reduce the latency of orders, we decided to offload some of these business validations from the OMS into an external component called Veto, which pre-validates incoming orders based on custom dynamic rules set by our Risk Management team. Rejected orders never go through to the OMS thereby reducing significant load on the OMS. This is the story of how we incrementally built this engine to keep up with the changing business and regulatory environment starting with a custom DSL (Domain Specific Language) and ending up with writing a framework to manage rules written in Go and embedded inside Go plugins.

Overview

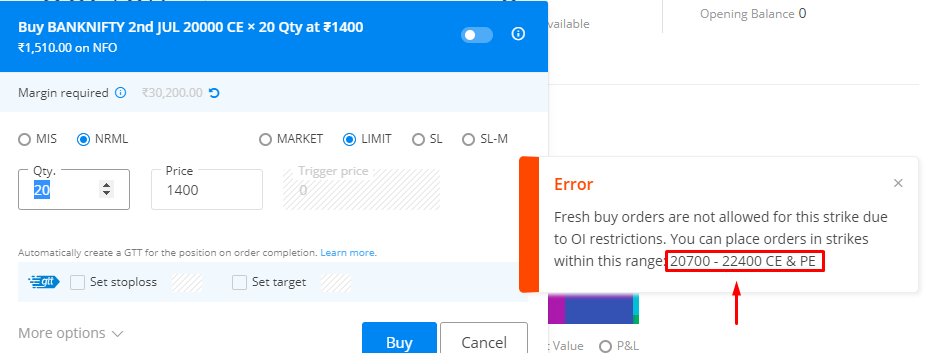

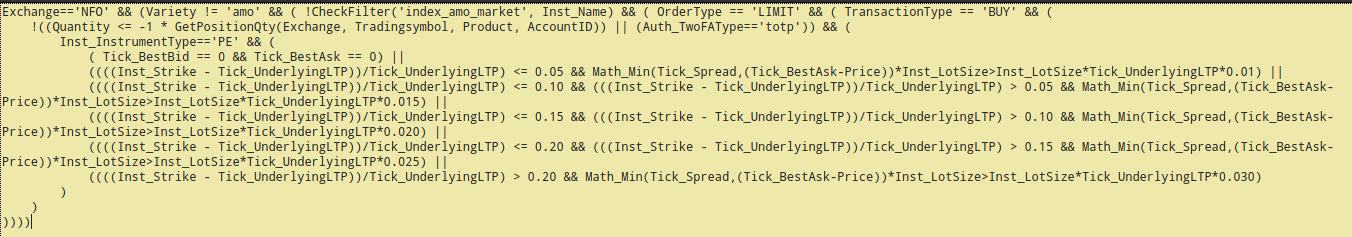

Our goal with Veto was to build a dynamic evaluation engine framework capable of hot-reloads. This framework would provide a generic environment to manage, track and audit rules and filters on an easily accessible dashboard. The engine should have support for custom data-stores related to the orders. Rules in this framework are business validations on orders placed by our clients. These validations range from simple checks like validating the limit prices to be within circuit limits, to complex beasts, which validate fresh buy orders in Nifty/BankNifty strikes due to exchange OI restrictions.

Our first solution utilized our research from the Sentinel project. We combined knetic/govaluate, which is an expression evaluation engine, along with a filter manager and a hot reload mechanism with an HTTP server which would either respond with an appropriate rejection to the incoming order or proxy to the upstream OMS, thereby acting as a reverse proxy with validations. The expression language was similar to Excel formulas, which was familiar to our RMS Team that managed and operated it through custom management dashboard built using Frappe/ERPNext.

Problems with DSLs

After taking it live, we realized a bunch of issues that cropped up and became pain points for us over time. These were not really technical, but more or less, human usability issues.

Since the underlying engine was a simple expression evaluator, the operators would end up spending hours trying to write complex rules, and similarly the developers, who are supposed to approve the rule to be production ready, spent time reviewing it.

This was due to how unreadable the expressions would become beyond a certain complexity. Simple rules were indeed faster to write, but anything beyond it would be beyond human capability to comprehend, which would cause unnecessary and difficult debugging sessions in the office.

Unlike a regular language with branching, the operator writing the rule would be stuck on writing logic defined with bracket matching and

AND/ORstatements. Also, missing support for variables would not allow us to reuse values.To write a single complex rule, operators would depend on writing the rules into manageable chunks. For example, a single spread (shown below) the rule would be broken into

spread_ce_buy,spread_ce_sell,spread_pe_buy,spread_pe_sellrules.

Custom error messages and any non-boolean behaviour were not possible, as the expression can only evaluate to a boolean. Switching to a proper language, we could use early returns in the rule and return custom messages alongside the evaluation result.

Implementing new functions and adding new variables was a pain.

- This meant that if you were to add a new function, you would have to bundle it within the engine, defeating the purpose of the rules being dynamic.

- This also meant the developer had to always be involved in writing the rules, defying the whole purpose of having a DSL for business folks.

New beginnings

Our learnings from these issues made us reflect if it would be worth it for the

operators to keep using a simple expression language. The way we were going, we were

essentially building a DSL (Domain Specific Language) on top of govaluate,

that would keep getting more complex with time.

We finally decided that a solution to the problem was to use Go-like language as

the DSL instead of govalute and distribute the dynamic rules as Go plugins, as

Veto was written in Go in the first place, just like the rest of the Kite stack.

It is simple, easy to learn, and has good tooling around it.

We debated heavily on the best approach to solve the problems that we were facing with veto rules and shortlisted a few candidates. We picked a complex rule in production written using govaluate and wrote that in the following to benchmark the performance of the rules in the alternatives.

- Govaluate - evaluates arbitrary C-like expressions

- Yaegi - embedded go interpreter

- Rego - open-policy-agent DSL

- Hashicorp Plugins - plugin system over RPC.

- go-plugins - native go plugins

Benchmark Results:

govaluate:

1319773 907 ns/op

go-plugins:

2745398 503 ns/op

yaegi:

202173 11091 ns/op

rego:

83476 13796 ns/op

We considered govaluate to be the baseline for our experiments. In our benchmarks, native plugins outperformed other solutions and brought the power of the entire Go runtime into independent plugins. We discarded Hashicorp plugins, as they were slower. Yaegi was nice, but not as fast as govaluate. Govaluate and Yaegi provide a simpler way to distribute rules, when compared to native plugins which need a bit of orchestration.

Veto v2

Considering all the facts, we decided to go ahead with native Go plugins. They are as fast as native code once loaded, and given enough tooling, act just like regular Go code, along with all its niceties like type safety and none of the baggage of other alternatives.

Veto v2 would be a web server which loads rules from native Go plugins on boot and behave like a reverse proxy accepting incoming orders as HTTP requests, either rejecting them in place or proxying them to the upstream OMS.

Since there are problems associated with building and distributing plugins due to dependency issues, requiring in-tree building and compilation, we decided to first work on writing a framework to abstract the caveats associated with go plugins.

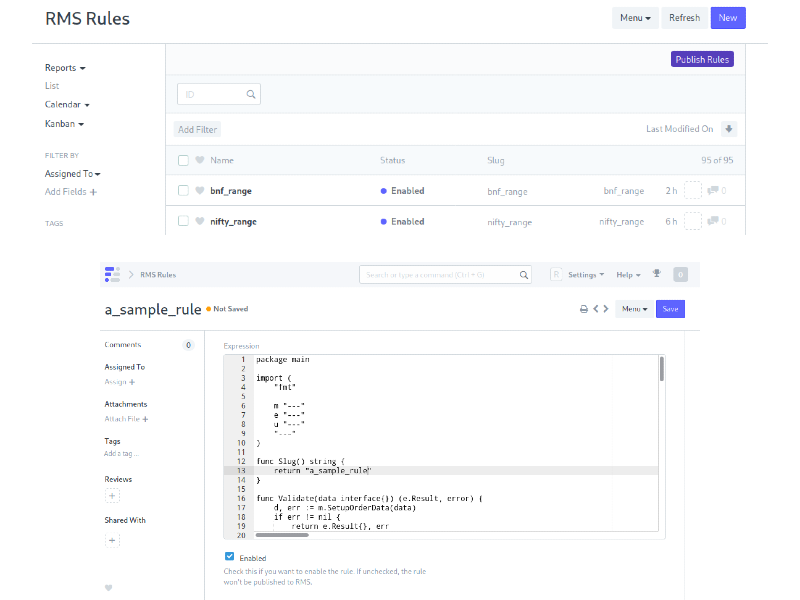

A framework for writing rules

Rules in Veto v2 are now written in plain Go by the operators. A rule looks similar to the following sample rule.

Each rule is expected to provide three functions.

Rules are contained in the Validate functions that are expected to accept an

interface and return a rule.Result. The contexts contain the controllers and

data needed for validating the rule, and are passed by the host to the rule

manager which iterates over all the rules. The host can then interpret the result

and do what it needs to, in our case render a response to the user with a custom

message, or proxy to the upstream.

Another added benefit of having written a custom go plugin based framework for

rules, is that we can implement our own testing framework for validation of the

rules. Every rule is expected to return its own testcases as a

map[interface{}]e.Result where the interface is the context. This way if a

rule implements all the testcases, we are sure that any minor refactor will be

also correct in the future. This reduces the need for constant developer

oversight and the testing needed for the rules. Also, the testcases provide

extra documentation for the future.

The following rule contains a sample circuit limit rule for illustration.

package main

import (

...

)

// Slug is the identifier for the rule. Used in statistics and logging.

func Slug() string {

return "a_sample_ckt_limit_rule"

}

// Validate, is where the validation logic resides.

func Validate(data interface{}) (e.Result, error) {

d, err := m.SetupOrderData(data)

if err != nil {

return e.Result{}, err

}

...

// Get the market for the incoming order

s, err := d.Ticker.GetSnapForOrder(d.OrderData.Order)

if err != nil {

return e.Result{}, err

}

...

// Check limits

if d.Order.Price > s.UpperCircuitLimit {

return e.Result{

Result: true,

Message: fmt.Sprintf(

"Your order price is higher than the current [upper circuit limit](https://support.zerodha.com/category/trading-and-markets/trading-faqs/articles/what-does-circuit-limits-i-e-price-bands-mean) of %g. You can place an order within the range or [use GTT](https://support.zerodha.com/category/trading-and-markets/gtt/articles/what-is-the-good-till-triggered-gtt-feature) for long-standing orders.",

s.UpperCircuitLimit),

}, nil

}

if s.LowerCircuitLimit > d.Order.Price {

return e.Result{

Result: true,

Message: fmt.Sprintf(

"Your order price is lower than the current [lower circuit limit](https://support.zerodha.com/category/trading-and-markets/trading-faqs/articles/what-does-circuit-limits-i-e-price-bands-mean) of %g. You can place an order within the range or [use GTT](https://support.zerodha.com/category/trading-and-markets/gtt/articles/what-is-the-good-till-triggered-gtt-feature) for long-standing orders.",

s.LowerCircuitLimit),

}, nil

}

return e.Result{}, nil

}

// TestData is expected to be provided by the rule,

// so it can be validated before it is allowed to be published.

func TestData() map[interface{}]e.Result {

tckr := &ticker.Ticker{

Data: map[string]interface{}{

"NSE:INFY": snaps.Snap{

LastPrice: 12.34,

UpperCircuitLimit: 15.0,

LowerCircuitLimit: 10.0,

},

},

}

return map[interface{}]e.Result{

&m.OrderContext{

Controllers: m.Controllers{

Ticker: tckr,

},

OrderData: m.OrderData{

Order: oms.OrderParams{

Exchange: "NSE",

Tradingsymbol: "INFY",

Price: 20.34,

OrderType: "LIMIT",

},

},

}: e.Result{

Result: true,

Message: "Your order price is higher than the current [upper circuit limit](https://support.zerodha.com/category/trading-and-markets/trading-faqs/articles/what-does-circuit-limits-i-e-price-bands-mean) of 15. You can place an order within the range or [use GTT](https://support.zerodha.com/category/trading-and-markets/gtt/articles/what-is-the-good-till-triggered-gtt-feature) for long-standing orders.",

},

}

}

Overcoming Go Plugin Caveats

Using Go plugins in your projects comes with a lot of caveats. As of writing, there hasn’t been much development on the feature recently. The commit history shows us that the last major commit happened nearly 2 years ago. On the gopher slack, the sentiment, more or less, is that this is not a priority anymore. Along with this, there are multiple issues that come up with maintaining projects that use it:

- The Go version for both host program and plugin should match exactly.

- External dependencies should match.

- Host and plugin GOPATH needs to exactly match while building.

- Plugins cannot depend on interfaces or structs of the host without in-tree building.

- Plugins can’t be un-loaded after they have been loaded by the host.

- An exactly same plugin cannot be loaded again by the host.

To learn more you can read this issue summarising some of the problems with go plugins.

Plugins works well if the projects bundles all the plugins in its own source tree and both the host and plugins are built together at the same time. But, that might limit the scope of a project. Externally maintained plugins are near to impossible to build independent of the host program.

Building rules

To solve the issues listed above, we can use Docker to build both the host program and our custom plugins together. Using Docker, we are able to use emulated paths. This image also contains the source code of the host program. This image allows us to build and load the plugins separately from different machines, such as our CI/CD pipeline or a rule compiler as described further down the post.

In practice, we prepend the following dockerCommands, so that the

paths to the go build command.

// Commands for locally testing with docker. Prepended to buildCommands

// if dockerMode is enabled.

dockerCommands := []string{

"docker", "run",

"-v", pwd + "/bin/temp/go:/go", // Reduce the time for building

"-v", pwd + ":/usr/src/app", // Mock the paths

"-w", "/usr/src/app",

"golang:1.14",

}

buildCommands := []string{

"go",

"build",

"-ldflags",

"-s -w",

"-buildmode=plugin", // Required to build plugins

"-o",

outputFilePath,

inputFilePath,

}

Compiling rules

To combine multiple rules into a single plugin, we introduce the concept

internal to our project called Compilation. A compilation step is similar to the

build step, but combines multiple .go rule files which are stored in a folder

into a single .so plugin.

The compilation command expects a folder containing the source code of all the

rules, and the description.go which contains the meta information about what

would be available in the rule.so file. It utilizes the build steps described

in the section above, but adds pre-processing steps that help avoid a few of the

Go plugin caveats.

As per our framework, every rule is expected to provide three functions to compile. These are in turn used by the validation pre-process to verify the rule.

Plugins can export any kind of data and functions from their source. Since, multiple rules need to export the same function, while compiling all the rules into the plugin, we traverse through the AST and modify the function names and prefix the rule name.

AddPrefixToSource is a function that prefixes the rule name onto the functions

so they can be uniquely found when we load the plugin. For example, a rule with

slug as a_sample_rule will be available in the plugin as

E_a_sample_rule_Validate.

func AddPrefixToSource(prefix string, src []byte) ([]byte, error) {

fset := token.NewFileSet() // positions are relative to fset

node, err := parser.ParseFile(fset, "", src, 0)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

for _, f := range node.Decls {

fn, ok := f.(*ast.FuncDecl)

if !ok {

continue

}

if in(fn.Name.Name, allowedFunctionNames) {

fn.Name.Name = Export + prefix + "_" + fn.Name.Name

}

}

var b bytes.Buffer

buf := bufio.NewWriter(&b)

printer.Fprint(buf, fset, node)

buf.Flush()

return b.Bytes(), nil

}

Another function called AddTimestampToSource is used in the pre-processing to

enable realtime reloading of the plugin. Since Go currently can’t unload a

shared library, we must load unique plugins in long running programs. This

becomes a problem when we try to reload a plugin. This function makes the

compiled rule unique, allowing it to be reloaded with the same name and same

contents as well.

func AddTimestampToSource(src []byte) []byte {

ct := time.Now().UnixNano()

src = append(src, []byte("\n")...)

src = append(src, []byte(

fmt.Sprintf("const timestamp_%d = %d",

ct, ct))...)

return src

}

A rule .so file should be standalone. It should contain all the information

needed to know the contents of the plugin. Using another step, we create a

description about the contents of the plugin, and load it among the symbols of

the exported symbols of the plugin.

descFilePath := tmpSrcPath + "description.go"

descFile, err := os.Create(descFilePath)

if err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("opening description file: %w", err)

}

prefix := `package main

func Description() []string {

return []string{`

fmt.Fprintln(descFile, prefix)

for _, rname := range rnames {

_, err := fmt.Fprintf(descFile, `"%s",`, rname)

if err != nil {

return err

}

}

suffix := ` }

}

`

fmt.Fprintln(descFile, suffix)

Now, the host can use the following DecompileRules function and obtain all the

rules contained in the plugin.

func DecompileRules(rulePluginPath string) (map[string]func(interface{}) (rule.Result, error), error) {

...

d, err := p.Lookup("Description")

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

...

}

Dashboard for the operators

We connect two services with our admin dashboard implemented in Frappe where the operators can edit the rules. This panel has a built in editor, where the operator can edit the rules, validate it, and if it passes the test cases, it is saved to the database.

These are backed by two small deployments which run in an internal K8s instance with the validation and compiler veto servers.

The validation server has a handler which expects the rule source as a post

param. It adds a constant with the current unix timestamp to the source and

builds and validates the rule. If it passes, it returns true via an HTTP

response. In case of a failure, it records the stdout and responds with why it

failed, including the full Go build log, helping the operators know what

happened.

Our compiler server is responsible for listening on an endpoint for a post request which initiates a sync with the admin panel and then runs the compile rules routine on the folder and builds the plugin in the appropriate mock folder. Then we push this built plugin to our production veto instance and issue a hot-reload.

Conclusion

The major lesson here is that DSLs are complicated and clever choices can become human usability bottlenecks in the long run. Excel like familiarity in the expressions might let operators write and manage rules with ease, but becomes a pain overnight as the business rules and their complexities start growing out of control. A language like Go, which is simple, reliable, and efficient, is easier to learn for the operator than a custom DSL, and the sheer extensibility for the developer. Trusting non-tech folks to learn Go instead of investing in learning a custom DSL is a viable alternative that we have been able to successfully implement at India’s largest stock broker. Writing a framework that abstracts the annoying caveats of an under-loved feature like Go plugins, to enable dynamic loading of Go functions to act as rules, is useful, considering the tangible benefits it presents when compared to writing custom DSLs.