TL;DR Like numerous other orgs, we transitioned (actually, flipped overnight) to being fully remote during the first COVID pandemic lockdown in 2020. It worked out great in the first year, started losing its sheen in the second year, and became detrimental to creativity and collaboration by the third year. It failed for us in the most critical areas. We then made the collective decision to switch to a “hybrid” mode, where about 10% of us involved in creative and decision-making endeavours now come to the office three days a week while 90% of us continue to be fully remote.

The hard lesson we learnt is that effective, long term remote work requires specific skill sets and DNA to pull off.

Prelude

When the first COVID lockdown was announced in March 2020, Zerodha, like many organisations, transitioned to full remote work overnight—a 1000+ people spread across various departments including our small tech team. Thankfully, all the common sense technical and process pieces we had built over the years clicked into place and ensured this happened relatively smoothly—“zero-trust” networks with 2FA, cloud telephony for customer support calls, role-based access controls for all employee systems, and internal processes that could be migrated online, amongst others.

For the major part of the first year of the lockdown, we were all glued to our screens with nowhere else to go. This also happened to be the period when interest in capital markets exploded, pushing activity in stock markets to record breaking heights. During the pandemic induced uncertainty’s war-time-like atmosphere and the confinement to screens and four walls, productivity went through the roof. Everybody was on their toes and clued in on everything, almost perfectly in sync with each other—highly unsustainable and even unnatural over the long term, of course. Teams scrambled and transitioned to using online text chat, organising discussions in chat rooms, phone and video calls, getting stuff done. In the tech team, like clockwork, we fixed, changed, refactored, added, and shipped.

Then came the dreadful “second wave”, bringing untold misery and agony to countless people. Its direct and indirect effects that seem to have spared no one, manifested as mental trauma to people all around us, including me. Then, the lockdowns eased and humanity started to slowly stumble back and re-adjust to the post-COVID life.

And that’s when any early excitement and any magic of the unsustainable war-time like atmosphere of the abruptly adopted remote work model started wearing off. I witnessed this first-hand within our flat teams where people have sat, worked together, endured tough times, and had fun for the better part of a decade. It came in waves, as a stark reminder of how complex and nuanced human relationships are, and what it truly takes for a group of humans to stick together, converse freely, collaborate, all the while being happy enough to build a good org. And for an organisation whose foundation—whose very DNA—is built on human relationships, free flowing conversations, and spontaneity, this was close to damning.

We shipped more mega projects than ever, executed some of the riskiest large scale upgrades and migrations in our history, all the while working remotely. We did all of that, but at what cost? The human toll was significant. Isolation got to a number of people and adversely affected their mental wellbeing. The increasingly transactional nature of online work-communication was joyless. I found myself turning into a counsellor doing an ever increasing number of 1:1 personal conversations. It only ever escalated.

Then, a part of me just burnt out. Not from work, not from ever increasing complexity of our endeavours, not from regulatory pressure (endemic to the industry we are in), but from my dawning the hat of a counsellor. Within our tiny tech team, I found myself spending ever-increasing amounts of time trying to fix the widening gaps in communication and understanding stemming from lost nuance in English chat rooms and pixelated, tiled video screens. People in an org being reasonably happy, or at least not-unhappy, is as important as getting stuff done. As communication became increasingly task-oriented, terse, and transactional, as individuals started drifting apart, as spontaneity became rare, as collaboration transformed into task assignments and shipped code, as fun, lively voices and banter faded into silence of matter-of-fact chat rooms and soulless scheduled video calls with pixelated faces, as mental states of people around me degraded, a part of me burnt out.

As we do with all major decisions at the org, we talked, mulled over, debated, and argued about all of this. This particular debate went on for months until we had a majority consensus. There was heartache amongst a few, but the majority saw and concurred with the very visible adverse effects of being fully remote and detached.

We bit the bullet. We would come back to the office, three days a week, specifically for people to mingle, for voices to be heard, for conversations to be had, for spontaneity to arise, for decision-making to be participatory. That the significant majority of us live within a reasonable distance of the office and never moved away, was a huge relief.

And so, we came back, some 10% or about 100 of us in the org—technical, creative, business, and critical decision-making teams—on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays. Two days at home to zone-out, avoid commuting, and to do focused work, and three days specifically for conversations and collaboration across teams. We also introduced a fixed number of annual work from home days an individual could use to plan their year better.

This was sometime last year. Within a couple of months, the communication chasm had dissipated almost entirely. Decisions that would take days and weeks to slowly transpire online started happening in minutes. The unbearable and unreasonable coordination overhead of online “async” communication effectively vanished. Just walk over or turn around and ask someone in any language that works in that context—in all its glory, nuance, and expressiveness—not just in text messages. Breakthroughs stemming from spontaneous ideas and overheard conversations, a trait that has defined Zerodha’s journey, returned. Most importantly, the conversations, fun, and banter, restarted. The voices who were never comfortable speaking online or had trouble expressing themselves in chats, were heard again. And boy, wasn’t that heartening!

Zerodha is an org where people sit together, laugh, discuss, debate, and collaborate, where spontaneity serves the crucial role of being a facilitator. Our stint with fully remote work served as a stark reminder that the way we have built the org over the years, physical human proximity is key to its growth. That is a strong trait that we have hired for. As the significant positive effects of a small group of human beings sitting together over the last many months serve as a growing body of evidence (I mean, that is how the org always was), I am able to reflect on how it all went down for us.

This is of course very Zerodha-specific and I cannot comment on massive orgs or places where people hate the thought of walking into the office. I definitely cannot comment on orgs that surveil mouse movements or keystrokes as parameters for deciding whether people are “working” and being “productive”. Or worse, orgs that mandate webcams to surveil every move of an employee. There are far bigger systemic issues at play in such places. For orgs with small collaborative teams, our lessons may be relatable.

As I write this though, this very moment, I realise the great irony in my own personal history. I first went online and started tinkering with code in my early teens. For more than a decade in my formative years, every hobby project I worked on, every paid project I did, almost every person that I collaborated with, was fully online and remote—faceless chat and e-mail handles from all across the world. Innumerable textual conversations. My entire mental foundation was that of online, remote work. It still is for all my hobby open-source projects. Sitting in a room full of people, thus, was a really weird thought for me, which gradually changed at Zerodha as we slowly built a conducive environment.

How can something as fundamental as the mental model for similar kinds of work make sense in one context but not in another? It is weird, but then again, like most things in life, it is a trade-off and not an absolute.

Async

Async (asynchronous) is a key tenet of remote work, especially in software development and engineering. In an async setup, participants do not all have to be online simultaneously and are free to largely work according to their own schedules. Communication also becomes async, where participants are not expected to respond in realtime to messages. This model works well for collaboration on open-source projects and work that is fundamentally asynchronous. It does not work well for orgs that are inherently synchronous like Zerodha, even in engineering.

For us, the stock exchanges open at a specific time on a given day, and from then on, process orders collected from participants like us, sequentially. Exchanges in capital markets thus move ahead, one trade at a time, by the nanosecond, until they close at a given time. In a stock brokerage like Zerodha, there is significant amounts of data crunching and a large number of complex financial settlements which have to be completed within hours before the subsequent day’s market opening. Highly time-sensitive processes with no room for errors or delays.

Capital markets, thus, conceptually and physically, are not compatible with an async style of work. Decisions, interventions, and changes are highly time-sensitive, be it technical or regulatory. Often, every second counts and cuts across departments and teams in realtime. The significant majority of communication and work at Zerodha, and similar organisations riddled with extreme complexity, have to be sync and any lapses carry extremely high risk.

I have seen that software developers are particularly susceptible to not understanding the fundamental sync vs. async nature of orgs, often incorrectly drawing direct comparisons to software development async “pull request” workflows. Software development workflows do not necessarily translate to the level of an org.

Text chats in the Indian context

In our small tech team alone, there are about ten different native tongues, and English, for most of us, is our third or even fourth language. This is a killer feature of diverse Indian teams where the many valuable ethnolinguistic and cultural perspectives are easily transpiled and understood thanks to the shared underlying Indian-ness. English acts as a handy, neutral glue language. At Zerodha, in-person in the office, communication happens in a mix of English and native languages with people naturally deciphering subtle, unspoken cues and information from facial expressions and body language—you know, natural human communication, not rocket science.

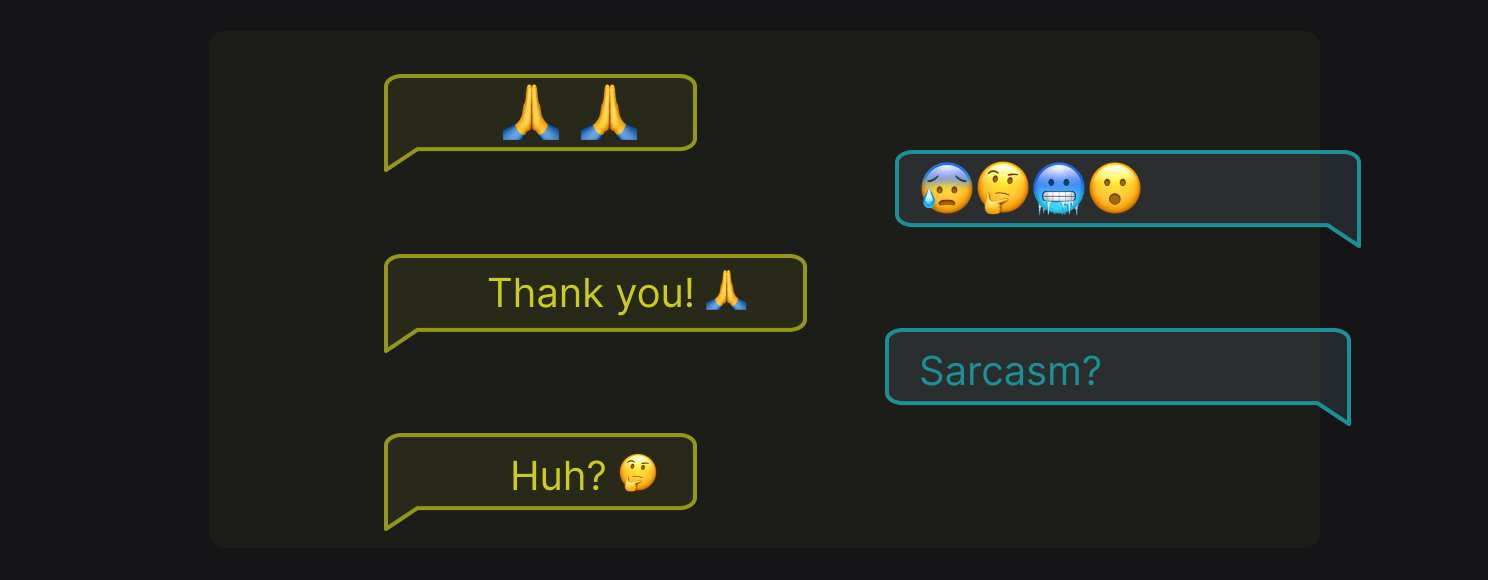

Also, we have never hired anyone based on their ability to quickly articulate and type out their thoughts in English with the specific knack of being able to engage in rapid back-and-forth text chats—a prerequisite for effective remote communication in the highly diverse Indian context. In our chat rooms, people who have this particular ability inadvertently ended up overshadowing people who were not adept at rapid text chats. There were even instances where misinterpreted emojis changed the trajectory of certain tasks—yep.

Those voices eventually started fading from the chat rooms. Their communications became transactional and reduced to only what was required for their specific tasks at hand, a perilous outcome for an org whose foundation is built on conversations and collaboration. I watched as the majority of voices faded despite encouragement and prodding.

Tools

Good remote communication is already really hard to pull off. If the tools that are meant to facilitate it do not provide a near-spotless user experience (UX), it can drive the participants mad. Poor threading on chat apps, laggy JS-bloated UIs that grind the system, delayed or missed notifications, potato quality videos, disconnections and reconnections, audio issues, buffering spinners, Ctrl + Shift + R, “Hold on. Let me try reconnecting” …

(ノಠ益ಠ)ノ彡┻━┻

We went through $n number of chat and video tools looking for ones that would give as seamless an experience as possible. For chat, we finally settled on a self-hosted version of Mattermost, which has worked out really well for us. Our experiments with Matrix clients were disastrous from a UX perspective and drove people insane. For video, we mostly used Google Meet which came with the organisational e-mail account anyway. Not perfect, but passable.

We have had an org-wide self-hosted Discourse forum open to all 1000+ employees from the pre-COVID times. Its usage skyrocketed during the COVID years and it became a thriving repository of information and async threads with participations from people from all departments. A lot of collective decision making happened there. Then, at a point, it just got overwhelming. Despite heavy categorisation, there were just way too many threads for people to keep track of. A forum fatigue set in.

In the daily deluge of e-mails, forums, chat rooms, multiple messaging apps, all day, every day—personal and professional—how does an average human being maintain context across so many communication channels, especially in very complex orgs? Moreso when they are almost completely devoid of the rich cues and nuances of face-to-face communication. No wonder that Zoom call fatigue [1] is now a phenomenon that is getting academic attention. I can only imagine the plight of people who are forced to use terrible communication tools picked by management who do not understand or care for UX[2].

I feel that, if anything, humanity is slowly reaching a point where we may have to make a conscious effort to reduce online communication and increase good old physical, face-to-face interactions.

Productivity

There is individual productivity, skill-building, growth, and excellence. There is also org-level productivity, skill-building, growth, and excellence.

Without the latter, without collective excellence in an org, there is no room for individual excellence, and very easily, no good org left for a motivated individual to excel or even work in. This is an understanding that does not come easily to young individuals at the infancy of their careers, where they are naturally motivated and fixated, and rightly so, on self-improvement and learning. Thinking about it, this is not evident to, or is entirely neglected by, seasoned professionals as well.

I noticed that working remotely, the sense of individual excellence slowly started triumphing over the sense of collective excellence, entirely unsurprisingly, thanks to the widening communications chasm. In a good org, the job of a software developer, for instance, is not just to develop good software or innovate or finish their tasks at hand. Their job is to also work with others around them and enable them to also do the same. Fluid, casual conversations and communication are essential to this. This cannot be a scheduled calendar item and has to flow naturally. In a good org, institutional memory is distributed across many individuals who are able to work reasonably well together.

Institutional memory

Institutional memory is a fascinating thing. In complex orgs, this ranges from everything from business and technical knowledge to untold cultural nuances that underlie decision-making, all spread out across many brains. An org is a brain of brains. Effective communication across them is what produces tangible outcomes. To add, institutional memory is often ever-evolving and fast changing, sometimes by the day. The probability of continued success of an org is rooted in their ability to ensure continuity of institutional memory with every successive generation—a Ship of Theseus of people.

While many orgs have the utopian goal of committing the entirety of institutional memory into neat documentation, knowledge maps, and wikis, I have come to realise that it is essentially a pipe dream. If we look around, rarely is an org able to copy another org’s culture or way of working. If everything could be accurately codified, they should be reproducible as well to a large extent. Rarely ever the case.

Rules can be codified, processes can be written down, systems can be documented, SOPs can be created, but despite all of that, it is only ever possible to document a small portion of institutional memory. What really makes an org tick simply cannot be textualised or documented. An org’s motto and philosophies can be written down on paper, but when people change, there is absolutely no guarantee that the spirit of the text passes on, or is even able to be interpreted in the same way.

So, what happens when rich, expressive communication that is the oil for the institutional memory machine is disrupted by high-overhead, broken, difficult-to-coordinate online communication with the aforementioned language barriers?

Unless an org has very specific, remote-first skill sets in its foundation, outlook, unless an org’s DNA itself is remote-first, collaborative, low-overhead communication is exceptionally hard to achieve over the long-term. It may be like attempting to retrofit a train to run without tracks.

Personal memory

In the course of our remote work experience, I have observed that discussions and decisions in reams of group text chats and pixelated video calls, over a period of time, become indistinguishable from each other in personal memory. Many in our org concur. On the other hand, lively group discussions and decisions tend to be remembered and recalled far better thanks to the numerous additional cues—people, faces, emotions, surroundings and environment, spontaneous moments. Needless to say, quality conversations to aid better recall of personal memory is crucial for inference from the collective institutional memory in decision-making and acts of creativity.

I will leave this as an anecdotal observation. If one is inclined to explore the scientific basis for some of these observations, concepts of social facilitation, episodic memory formation, mirror neurons etc. will make for very interesting reads.

Remote-first skill sets

So, what are some of the specific skill sets that are essential to making effective, long-term remote work sustainable? Assuming that an org:

- Is non-toxic and has an environment in which its participants are reasonably happy or at least not unhappy.

- Has work that is fundamentally remote-compatible and as a bonus, is also async-compatible.

- Is involved in creative, collaborative, and innovative endeavours.

- Has teams that are highly participatory.

To increase the probability of successfully pulling off long-term remote work, the org should adopt a remote-first lens when formulating its processes, teams, and culture. When hiring, it should look for these specific skills and traits in people:

- Ability to do effective, fast, back-and-forth 1:1 and group textual communication.

- Ability to be concise and expressive in the confines of online written, voice, and video communication.

- A knack for being conversational, beyond tasks, with peers on online mediums.

- An inclination and respect for digital etiquette.

- A good understanding and grasp of remote coordination.

- A knack and patience for documentation writing. Copious amounts of documentation really.

- Ability to be focused and be productive in isolation and in arbitrary environments.

At Zerodha, nobody was ever hired with these specific skills or traits. I personally struggle with some of these myself. We realised that the hard way that the creative, innovative, and decision-making side of Zerodha does not have a remote-work-first DNA or skills, and to top it all, the nature of the business and the risk involved makes it even more complicated.

That said, for the vast majority at the org—about 90% or about 900+ people—like our large support team, the dynamics are different. They continue to work remotely. Interestingly, amongst this group, a couple of hundred people voluntarily come to our offices, prefering that over working remotely from their respective homes or hometowns.

The logistical difficulties of offline congregation is a reality, especially in a city like Bangalore where, amongst other things, commuting is a nightmare. And yet, 10% of the org deciding to come back to the office is a trade-off that has turned out to be a positive one. Ultimately, no online medium is a substitute for natural, fluid, in-person interactions amongst a group of humans who get along reasonably well—at least until a dystopian AR/VR/Matrix-style world arrives.

- So, is remote work inherently bad? Of course not.

- Is it universally applicable to all contexts? Absolutely not.

- Is it hard to pull off? Yes.

- Did it fail for us in critical areas because of our lack of remote-first skills? Yes.

- Did we try to make it work? Yes. We tried really hard.

- Is it the end of the world for us? Not at all. Different things work for different orgs.

- Am I personally done with remote-text-chat-async-Zoom-first way of org building? Absolutely.

Afterword

And then, a furious Karan, our resident keyboard warrior (who is actually very adept at remote work in his defence), typed out “bUt MuH AsYnC” on an overly loud mechanical keyboard. His fury was not because async did not work out for us, but because every keystroke of his suffered from a crippling 600ms lag thanks to his overengineered “homelab” running on a RaspberryPi connected to a 4G dongle tied to a bamboo pole sticking out of his bedroom window, routing network traffic through strategically placed Tailscale nodes around the world. A contraption, for which, to this day, he has been unable to give us a convincing explanation.

Update (September 2024)

Every August, we conduct structured 1:1 conversations and reflections within the team, the culmination of many natural the ad-hoc 1:1 conversations that occur throughout the year. It has also been a year since we transitioned back to working from the office–three days in the office, two days at home. This time around, ~90% of the team reported that mentally, they are doing well, or at least okay. This is strikingly different from last year when ~80%, including me, reported not being in a good place mentally. Over the course of this year, mentally, I have also been in a much better place. Within the team, I have had to do practically no counselling conversations, which were almost a weekly occurrence in the past year. Our collective productivity has increased significantly and our interpersonal relationships are in much healthier place. The spontaneous, natural, in-person conversations and cohesion, as they always had for us, are resulting in unplanned, exciting engineering and product breakthroughs. The vast majority of the team report significant improvements in their personal and work lives, and that is indeed visible in many ways. We are laughing, having fun, and hacking substantially more. A recent discussion we had in the office has finally pushed me over the edge into hacking and assembling a serious “homelab” server. After years of meme-ing Karan, I am becoming the meme. Karan wins. Reminiscing Oppenheimer, “I am become Karan, the builder of homelabs.”

At Zerodha, our internal lessons now have a big body of evidence to go along. Long-term remote work requires specific remote-first skill sets and DNA from day one, which, like most other organizations, we do not possess for various historical reasons. So, we follow the optimal, least-wrong model that works for us—the organisation and its people.